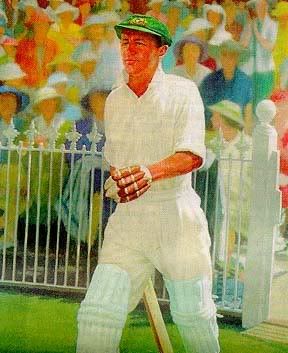

Sir Donald George Bradman, AC (27 August 1908—25 February 2001), often called The Don, was an Australian cricketer, generally acknowledged as the greatest batsman of all time. Later in his career he was an administrator and writer on the game. Bradman is one of Australia's most popular sporting heroes, and one of the most respected past players in other cricketing nations. His career Test batting average of 99.94 is by many measures the greatest statistical performance in any major sport.

The story of the young Don practising alone with a cricket stump and a golf ball is part of Australian folklore. Bradman’s meteoric rise from bush cricket to the Australian Test team took just over two years. Before his 22nd birthday, he set myriad records for high scoring (many of which stand even today) and became Australia's sporting idol at the height of the Great Depression. A controversial set of tactics, known as Bodyline, were devised by the England team to curb his batting brilliance.

During a twenty-year career, Bradman consistently scored at a level that made him "worth three batsmen to Australia". Committed to attacking, entertaining cricket, Bradman drew spectators in record numbers. He found the constant adulation an anathema, however, and it affected how he dealt with others. The focus of attention on his individual performances strained relationships with some team-mates, administrators and journalists, who thought him aloof and wary. After World War II, he made a dramatic comeback and in his final season captained an Australian team known as "The Invincibles". RC Robertson-Glasgow wrote of the English reaction to Bradman's retirement that, "... a miracle has been removed from among us. So must ancient Italy have felt when she heard of the death of Hannibal."

A complex, highly-driven man, not given to close personal relationships, Bradman maintained his pre-eminence by acting as an administrator, selector and writer for three decades following his retirement. His opinion was highly sought, but, in his declining years, he became very reclusive. However, his status as a national icon was still recognised, with the then Prime Minister of Australia, John Howard, calling him the "greatest living Australian". His image has appeared on postage stamps and coins, and he became the first living Australian to have a museum dedicated to his life.

Donald Bradman was the youngest child of George Bradman and his wife Emily (nee Whatman) when he was born 27 August 1908 at Cootamundra, New South Wales (NSW). He had a brother, Victor, and three sisters - Islet, Lilian and Elizabeth May. The family lived in nearby Yeo Yeo. When Bradman was about two-and-a-half years old, his parents moved to Bowral in the NSW Southern Highlands for the cooler climate.

Bradman practised batting incessantly during his youth. He invented his own solo cricket game, using a cricket stump for a bat, and a golf ball. A water tank, mounted on a curved brick stand, stood on a paved area behind the family home. When hit into the curved brick facing of the stand, the ball rebounded at high speed and varying angles -- and he attempted to hit it again. This form of practice developed his timing and reactions to a high degree. He hit his first century at the age of twelve, playing for the Bowral Public School against Mittagong High School.

Bush cricketer:

In 1920–21, he acted as scorer for the local Bowral team, captained by his uncle George Whatman, and once filled in when the team was short of players, scoring 37 not out. During the season, Bradman's father took him to the Sydney Cricket Ground (SCG) to watch the fifth Ashes Test match. On that day, Bradman formed an ambition. "I shall never be satisfied," he told his father, "until I play on this ground."

In 1922, he left school to work for a local real estate agent who encouraged his sporting pursuits by giving him time off when necessary. For two years, Bradman gave cricket away in favour of tennis.

Bradman resumed cricket in 1925–26, when several outstanding performances earned him the attention of the Sydney daily press. Competing on matting-over-concrete pitches, Bowral played other rural towns as part of the Berrima District competition. Against Wingello, a team that included the future Test bowler Bill O'Reilly, Bradman made 234.[6] In the competition final against Moss Vale, which extended over five consecutive Saturdays, Bradman scored 300.

During the following winter, an ageing Australian team lost the Ashes in England, and a number of Test players retired. The New South Wales Cricket Association began a hunt for new talent. Mindful of Bradman's big scores for Bowral, the association wrote to him, requesting his attendance at a practice session in Sydney. Subsequently, Bradman was chosen for the "Country Week" tournaments at both cricket and tennis, to be played during separate weeks. His boss presented him with a fateful ultimatum: he could only have one week away from work, so he had to choose between the two sports.

Bradman's performances during Country Week elicited an invitation to play grade cricket in Sydney for St George, where he scored 110 on debut, his first century on a turf wicket. At New Year 1927, he turned out for the NSW second team. For the remainder of the season, Bradman travelled the 130 km from Bowral to Sydney every Saturday to play for St George. Making a last appearance for his home town in the final against Moss Vale, he hit 320 not out.

First-class debut:

The next season continued the rapid rise of the "Boy from Bowral". Selected to replace the unfit Archie Jackson in the NSW team, Bradman made his first-class debut at the Adelaide Oval, aged nineteen. His innings of 118 featured what soon became his trademarks - fast footwork, calm confidence and rapid scoring. In the final match of the season, he made his first century at the SCG, against the Sheffield Shield champions Victoria. Despite his potential, Bradman was not chosen for the Australian second team to tour New Zealand.

Bradman decided that his chances for Test selection would be improved by moving to Sydney for the 1928–29 season, when England toured in defence of the Ashes. Initially, he continued working in real estate, but later took a promotions job with the sporting goods retailer Mick Simmons Ltd. In the first match of the Sheffield Shield season, he scored a century in each innings against Queensland and then made 87 and 132 not out against England. This earned him selection for the first Test at Brisbane.

Test Career:

Playing in only his tenth first-class match, Bradman found his initial Test a harsh learning experience. Caught on a sticky wicket, Australia was all out for 66 in the second innings and lost by 675 runs. The selectors dropped Bradman to twelfth man for the second Test. An injury to Bill Ponsford early in the match required Bradman to field as substitute while England amassed 636, following their 863 runs in the first Test. RS Whitington wrote, “... he had scored only nineteen himself and these experiences appear to have provided him with food for thought”.

Recalled for the next Test at Melbourne, Bradman scored 79 and 112 to become the youngest player to make a Test century, but it was in a losing team. Another loss followed in the fourth Test. Bradman reached 58 in the second innings and appeared set to guide the team to victory when he was run out. It was the only run out of his Test career and the losing margin was just 12 runs.

The improving Australians broke through to win the final Test. Bradman top-scored with 123 in the first innings, and was at the wicket in the second innings when his captain Jack Ryder hit the winning runs. He completed the season with 1,690 first-class runs (at 93.88 average), and his first multiple century, 340 not out against Victoria in a Sheffield Shield match, set a new ground record for the SCG.

Bradman averaged 113.28 in 1929–30. In a trial match to select the team to tour England, he was last man out in the first innings for 124. As his team followed on, the skipper Bill Woodfull asked Bradman to keep the pads on and open the second innings. By stumps, he was 205 not out, on his way to 225. Against Queensland at the SCG, Bradman set a world first-class record by scoring 452 not out, in only 415 minutes.

Although he was an obvious selection to tour England, Bradman's unorthodox style raised doubt that he could succeed on the slower English pitches. Percy Fender wrote:

"... he will always be in the category of the brilliant, if unsound, ones. Promise there is in Bradman in plenty, though watching him does not inspire one with any confidence that he desires to take the only course which will lead him to a fulfilment of that promise. He makes a mistake, then makes it again and again; he does not correct it, or look as if he were trying to do so. He seems to live for the exuberance of the moment."

1930 tour of England:

England was favoured to win the 1930 Ashes series. Much Australian hope rested with the potential of Bradman and Archie Jackson. With his elegant batting technique, Jackson appeared the brighter prospect of the pair. However, Bradman started with 236 at Worcester in his first innings on English soil. He scored 1,000 first-class runs by the end of May, the fifth player (and first Australian) to achieve this rare feat. In his first Test appearance in England Bradman hit 131 in the second innings but England won the game.

His batting reached a new level in the second Test at Lord's where he scored 254 as Australia won and levelled the series. Bradman rated this his best innings as, “practically without exception every ball went where it was intended to go”. Wisden noted his fast footwork in “hitting all round the wicket with power and accuracy” and his faultless concentration in keeping the ball along the ground.

This performance was surpassed at Leeds: Bradman scored a century before lunch on the first day of the Test match to equal the performances of Victor Trumper and Charlie Macartney. In the afternoon, Bradman added another century between lunch and tea, finishing the day on 309 not out. He remains the only Test player to pass 300 in one day’s play. His eventual score of 334 (46 boundaries) dominated the innings as the second highest score was 77 by Alan Kippax. Businessman Arthur Whitelaw later presented Bradman with a cheque for £1000 in appreciation of his (then) world record score. The match ended in anti-climax as poor weather prevented a result, as it did in the fourth Test.

The dynamic nature of Bradman’s batting contrasted sharply with his quiet, solitary off-field demeanour. He was described as aloof from his teammates and he did not offer to buy them a round of drinks, let alone share the money given to him by Whitelaw. A lot of the quiet time Bradman spent writing, as he had sold the rights to a book.

In the deciding Test at The Oval England made 405. During an innings stretching over three days due to intermittent rain, Bradman scored 232, which helped give Australia a big lead of 290 runs. In a crucial partnership with Archie Jackson, Bradman battled through a difficult session when England fast bowler Harold Larwood bowled short on a pitch enlivened by the rain. Wisden gave this period of play only a passing mention:

On the Wednesday morning the ball flew about a good deal, both batsmen frequently being hit on the body ... on more than one occasion each player cocked the ball up dangerously but always, as it happened, just wide of the fieldsmen.

However, a number of English players and commentators noted Bradman’s discomfort in playing the short, rising delivery. The revelation came too late for this particular match as Australia won by an innings to regain the Ashes. The impact of the victory in Australia was immense. With the economy sliding toward depression and unemployment rapidly rising, the country found solace in sporting triumph. The story of a self-taught 22 year-old from the bush who set a series of records against the old rival made Bradman a national hero.

In all, Bradman batted for 24½ hours during the Test series, scoring 974 runs at an average of 139.14 with a strike-rate of 61.65. His first-class tally for the tour, 2,960 runs (at 98.66 with ten centuries), was another record. Both his total of 974 runs and his three double centuries in one Test series still stand as records today.

Bradman was unprepared for the intensity of his reception in Australia; he became a "reluctant hero". Mick Simmons wanted to cash in on their employee’s newly won fame. They asked Bradman to leave his teammates behind in Fremantle and organised official receptions in Adelaide, Melbourne, Goulburn, his hometown Bowral and Sydney, where he received a brand new custom-built Chevrolet. At each stop, Bradman received a level of adulation that "embarrassed" him. This focus on an individual in a team game, "... permanently damaged relationships with his contemporaries". Commenting Australia's victory, the team's vice-captain Vic Richardson said, “... we could have played any team without Bradman, but we could not have played the blind school without Clarrie Grimmett”.

Reluctant hero:

In 1930–31, against the first West Indian side to visit Australia, Bradman’s scoring was more sedate than in England, although he did make 223 in 297 minutes in the third Test at Brisbane and 152 in 154 minutes in the following Test at Melbourne. The South Africans didn’t get off so lightly in the summer of 1931–32. For NSW against the tourists, he made 30, 135 and 219. In the Test matches, he scored 226 (277 minutes), 112 (155 minutes), 2 and 167 (183 minutes), and a new Australian Test record of 299 not out at Adelaide. Australia won nine of the ten Tests.

In fifteen Test matches since the beginning of 1930, Bradman had scored 2,227 runs at 131 average. Ten of his 18 innings were centuries, six of them beyond 200. His scoring rate was almost 44 runs per hour, with 856 (or 38.5%) scored in boundaries. Significantly, he had not hit a six, which typified the Bradman attitude: if he hit the ball along the ground, then it couldn’t be caught. During this phase of his career, his youth and natural fitness allowed him to adopt a “machine-like” approach to batting. The South African fast bowler Sandy Bell described bowling to him as, “heart-breaking ... with his sort of cynical grin, which rather reminds one of the Sphinx ... he never seems to perspire”.

Between these two seasons, Bradman seriously contemplated playing professional cricket in England with the Lancashire League club Accrington, a move that would end his Test career. A consortium of three Sydney businesses offered an alternative. They devised a two-year contract whereby Bradman wrote for Associated Newspapers, broadcast on Radio 2UE and promoted the menswear retailing chain FJ Palmer and Son. However, the contract increased Bradman’s dependence on his public profile, making it more difficult to lead the private life that he ardently desired.

Hundreds of onlookers gather as the Bradmans leave the church after their wedding ceremony in 1932.Bradman’s wedding to Jessie Menzies in April 1932 was chaotic and epitomised how difficult his desire for privacy was to attain. The church “was under siege all throughout the day ... uninvited guests stood on chairs and pews to get a better view”, police erected barriers that were broken down and many of those invited could not get a seat. Just weeks later, Bradman joined a private team organised by Arthur Mailey to tour the United States and Canada. He travelled with his wife, and the couple treated the trip as a honeymoon. Playing 51 games in 75 days, Bradman scored 3,779 runs at 102.1, with 18 centuries. Although the standard of play was not high, the amount of cricket Bradman had played in the previous three years, and the strains of his celebrity status, began to show on his return home.

Bodyline:

"As long as Australia has Bradman she will be invincible ... In order to keep alive the competitive spirit, the authorities might take a hint from billiards. It is almost time to request a legal limit on the number of runs Bradman should be allowed to make."

—News Chronicle, London

Plum Warner was an influential voice within the MCC, the club that administered English cricket at the time. He wrote of Bradman that, “England must evolve a new type of bowler and develop fresh ideas and strange tactics to curb his almost uncanny skill". Warner orchestrated the appointment of Douglas Jardine as England captain in 1931, as a prelude to Jardine leading the 1932–33 tour to Australia, with Warner as team manager.

Perceiving that Bradman struggled against bouncers during his 232 at The Oval, Jardine decided to combine traditional leg theory with short-pitched bowling to combat Bradman. He settled on the Notts fast bowlers Harold Larwood and Bill Voce as the spearheads for his tactics. In support, the England selectors chose another three pacemen for the squad. The unusually high number of fast bowlers caused a lot of comment in both countries and Bradman himself suspected a virulent intent.

Bradman had several other problems to deal with at this time. Among these were random bouts of illness from an undiagnosed malaise which had begun during the tour of North America; and that the Australian Board of Control had initially refused permission for him to write for the press -- this dispute was eventually resolved after Bradman threatened to quit the game.

In three first-class games against England before the Tests, Bradman averaged just 17.16 in six innings. Jardine decided to trial the new tactics in only one game, a fixture against an Australian XI at Melbourne. In this match, Bradman faced the leg theory and later warned local administrators that trouble was brewing if it continued. He withdrew from the first Test at Sydney amid rumours that he had suffered a nervous breakdown. Despite his absence, England bowled Bodyline (as it was now dubbed) and won an ill-tempered match in which Stan McCabe scored a famous century.

Australia took a first innings lead in the match, and another record crowd on 2 January 1933 watched Bradman hit a counterattacking second innings century. His unbeaten 103 (from 146 balls) in a team total of 191 helped set England a target of 251 to win. Bill O’Reilly and Bert Ironmonger bowled Australia to a series-levelling victory amid hopes that Bodyline was beaten.

The third Test at Adelaide Oval proved pivotal. Angry crowd scenes occurred after the Australian skipper Bill Woodfull and wicketkeeper Bert Oldfield were hit by bouncers. An apologetic Plum Warner entered the Australian dressing room and was rebuked by Woodfull. The Board of Control, in a cable to the MCC, repeated the allegation of poor sportsmanship directed at Warner by Woodfull. England continued with Bodyline despite Australian protests, and with the support of the MCC. The tourists won the last three Tests convincingly and regained the Ashes. Bradman caused controversy with his own tactics. Always seeking to score, he often backed away and hit the ball into the vacant half of the outfield with unorthodox shots reminiscent of tennis or golf. This brought him 396 runs (at 56.57) for the series and plaudits for attempting to find a solution to Bodyline. However, others thought it proved the theory that he didn’t handle the short ball very well. Jack Fingleton was in no doubt that Bradman's game altered irrevocably as a consequence, writing:

Bodyline was specially prepared, nutured for and expended on him and, in consequence, his technique underwent a change quicker than might have been the case with the passage of time. Bodyline plucked something vibrant from his art.

Near death:

In his farewell season for NSW, Bradman averaged 132.44, his best yet. He was appointed vice-captain for the 1934 tour of England. However, his health continued to be variable. Although he again started with a double century at Worcester, his famed concentration soon deserted him. Wisden wrote:

"... there were many occasions on which he was out to wild strokes. Indeed at one period he created the impression that, to some extent, he had lost control of himself and went in to bat with an almost complete disregard for anything in the shape of a defensive stroke."

At one stage, Bradman went 13 innings without a century, the longest such spell of his career, prompting suggestions that Bodyline had eroded his confidence and altered his technique. After three Tests, the series was one-all and Bradman had scored 133 runs in five innings. The Australians travelled to Sheffield and played a warm up game before the fourth Test. Bradman started slowly and then, "... the old Bradman [was] back with us, in the twinkling of an eye, almost". He went on to make 140, with the last 90 runs coming in just 45 minutes. On the opening day of the Test at Leeds, England were out for 200, but Australia slumped to 3/39, losing the third wicket from the last ball of the day. Listed to bat at number five, Bradman would start his innings the next day.

That evening, Bradman declined an invitation to dinner from Neville Cardus, telling the journalist that he wanted an early night because the team needed him to make a double century the next day. Cardus pointed out that his previous innings on the ground was 334, and the law of averages was against another such score. Bradman told Cardus, "I don’t believe in the law of averages".

Bradman batted all day and into the next. His record partnership of 388 with Bill Ponsford decimated the English attack. When he was finally out for 304 (473 balls, 43 fours and two sixes), Australia had a lead of 350 runs. However, rain prevented Australia winning. The effort stretched Bradman’s reserves of energy, and he didn’t play again until the fifth Test at The Oval, the match that would decide the Ashes.

In the first innings at The Oval, Bradman and Ponsford recorded another massive partnership, this time 451 runs. Bradman’s share was 244 from 271 balls, and the Australian total of 701 set up victory by 562 runs. For the fourth time in five series, the Ashes changed hands. England would not recover them again until after Bradman's retirement.

Seemingly restored to full health, Bradman blazed two centuries in the last two games of the tour. However, when he returned to London to prepare for the trip home, he experienced severe abdominal pain. It took a doctor more than 24 hours to diagnose acute appendicitis and a surgeon operated immediately. Bradman lost a lot of blood during the four-hour procedure and peritonitis set in. With penicillin and sulphonamides still experimental treatments at this time, this was usually a fatal condition. On 25 September, the hospital issued a statement that Bradman was struggling for his life and that blood donors were needed urgently.

"The effect of the announcement was little short of spectacular." The hospital could not deal with the number of donors, or with the volume of telephone calls the news generated, so the switchboard closed. Journalists were asked by their editors to prepare obituaries. Teammate Bill O’Reilly took a call from King George’s secretary, asking that the King be kept informed of the situation.

His 270 runs won the match for Australia and has been rated the greatest innings of all time.Jessie Bradman started the month-long journey to London as soon as she received the news. En route she heard a rumour that her husband had died. A telephone call clarified the situation and by the time she reached London, Bradman had begun a slow recovery. He followed medical advice to convalesce, taking several months to return to Australia and he missed the 1934–35 season.

Internal politics and the Test captaincy:

There was off-field intrigue in Australian cricket during the winter of 1935. Australia, scheduled to make a tour of South Africa the following summer, needed to replace the retired Bill Woodfull as captain. The Board of Control wanted Bradman to lead the team. On 8 August, the Board announced Bradman's withdrawal from the team due to a lack of fitness, yet he led the SA team in a full programme of matches in the absence of the Test players. Vic Richardson, whom Bradman replaced as SA captain, was made Test captain, even though his record didn’t warrant a place in the Australian team.

Chris Harte's analysis of the situation is that a prior (unspecified) commercial agreement forced Bradman to remain in Australia. Moreover, Harte attributes an ulterior motive to his relocation. The off-field behaviour of Richardson and other SA players had displeased the SACA, which was looking for new leadership. To help improve discipline, Bradman became a committeeman of the SACA, and a selector of the SA and Australian teams. He took his adopted state to the Sheffield Shield title for the first time in ten years, scoring 233 against Queensland, followed immediately by 357 against Victoria. He finished the season with an SA record of 369 (in 233 minutes) against Tasmania.

Australia defeated South Africa 4–0 and senior players such as Bill O’Reilly were pointed in their comments about the enjoyment of playing under Richardson's captaincy. A clique of players who were openly hostile toward Bradman formed during the tour. For some, the prospect of playing under Bradman was daunting, as was the knowledge that he would be sitting in judgment of their abilities in his role as a selector.

To start the new season, the Test side played a rest of Australia team captained by Bradman at Sydney in early October 1936. The Test XI suffered a big defeat, due to Bradman’s 212 and a bag of twelve wickets by leg-spinner Frank Ward. Bradman let the members of the Test team know that despite their recent success, the team still required improvement. Shortly after, Bradman's first child was born on 28 October, but died the next day. He stood out of cricket for two weeks, then made 192 in three hours against Victoria in the last match before the beginning of the Ashes series.

The Test selectors made five changes to the team from the previous match at Durban. Australia’s most successful bowler Clarrie Grimmett was replaced by Ward, one of four players making their debut. The controversy over Grimmett’s continuing omission from the team dogged Bradman for the next two years – he was regarded as having finished the veteran’s Test career.

Australia suffered the worst of the weather conditions in the opening two Tests and crashed to successive losses. Bradman made two ducks in his four innings, and it seemed the captaincy was affecting his form. The selectors made another four changes to the team for the third Test at Melbourne.

On New Year's day 1937, Bradman won the toss, but again failed with the bat. The Australians could not take advantage of an easy wicket and finished the day at 6/181. Rain dramatically altered the course of the game on the second day. Bradman declared to get England in on the sticky wicket; England conceded a lead of 124 and declared to get Australia back in; Bradman countered by reversing his batting order to protect his run-makers until the wicket improved. The ploy worked and Bradman went in at number seven. In an epic performance spread over three days, he battled a dose of influenza and scored 270 off 375 balls, sharing a record partnership of 346 with Jack Fingleton[72] and Australia went on to victory. In 2001, Wisden rated this performance as the best Test match innings of all time.

At Adelaide, England had the upper hand in the next Test when Bradman played another patient second innings, making 212 from 395 balls. Australia levelled the series when the erratic left-arm spinner “Chuck” Fleetwood-Smith bowled Australia to victory. In the series-deciding fifth Test, Bradman returned to a more aggressive style in top-scoring with 169 (off 191 balls) in Australia’s 604. The weight of runs demoralised the opposition and an innings victory ensued. Australia's achievement of winning a series after going 0–2 down has yet to be equalled in Test cricket.

End of an era:

During the 1938 tour of England, Bradman played the most consistent cricket of his career. He needed to score heavily as England had a strengthened batting line-up, while the Australian bowling was over-reliant on O’Reilly. Grimmett was overlooked, but Jack Fingleton made the team, so the clique of anti-Bradman players remained. Playing 26 innings on tour, Bradman recorded 13 centuries (a new Australian record) and again made a thousand first-class runs before the end of May, the only player to do so twice. In scoring 2,429 runs, Bradman achieved the highest average ever recorded in an English season: 115.66.

In the first Test, Australia conceded a big first innings score and looked likely to lose when Stan McCabe played his classic knock of 232, a performance Bradman rated as the best he had ever seen. With Australia forced to follow-on, Bradman fought hard to ensure McCabe’s effort was not in vain, and he secured the draw with 144 not out. It was the slowest Test hundred of his career and he played a similar innings of 102 not out in the next Test as Australia struggled to another draw. Rain completely washed out the third Test at Manchester.

Australia’s opportunity came at Headingley, a Test described by Bradman as the best he ever played. England batted first and made 223. During the Australian innings, Bradman backed himself by opting to bat on in poor light when he had the option to go off, and he scored 103 out of a total of 242. The gamble paid off, as an England collapse left a target of only 107, but Australia slumped to 4/61, with Bradman out for 16. As an approaching storm threatened to wash the game out, Lindsay Hassett hit Australia to a victory that retained the Ashes. For the only time in his life, the tension of the occasion got to Bradman and he couldn’t watch the closing stages of play. This response reflected the pressure that he felt all tour: he described the captaincy as “exhausting” and that he “found it difficult to keep going”.

Ironically, the euphoria of Leeds preceded Australia's heaviest defeat. At The Oval, England amassed a world record of 7/903 and their opening batsman Len Hutton scored 364 to break Bradman’s Ashes record. In an attempt to relieve the burden on his bowlers, Bradman took a rare turn at the bowling crease. During his third over, he fractured his ankle, and teammates carried him from the ground. With Bradman and Fingleton unable to bat, Australia was thrashed by an innings and 579 runs, which remains the largest margin in Test cricket history. Unfit to complete the tour, Bradman left the team in the hands of vice-captain Stan McCabe. At this point, Bradman felt that the burden of captaincy would prevent him from touring England again, although he didn’t make this decision public.

Despite the pressure of captaincy, Bradman’s batting form remained supreme. An experienced, mature player now more commonly called “The Don” had replaced the blitzing style of his early days as the “Boy from Bowral”.[ In 1938–39, he led SA to the Sheffield Shield and made a century in six consecutive innings to equal the world record of CB Fry. From the beginning of the 1938 tour of England (including preliminary games in Australia) until early 1939, Bradman totalled 21 first-class centuries in just 34 innings.

The 1939–40 season was Bradman's most productive ever for SA: 1,448 runs at 144.8 average. Included in Bradman’s three double centuries was 251 not out against NSW, the innings that he rated the best he ever played in the Sheffield Shield as he tamed Bill O’Reilly at the height of his form. However, it was the end of an era. The worsening situation in Europe led to the indefinite postponement of all cricket tours, and the suspension of the Sheffield Shield competition.

Troubled war years:

Bradman joined the RAAF on 28 June 1940 and was passed fit for air crew duty. He bided time in Adelaide as the RAAF had more recruits than it could equip and train. Four months later, the Governor-General of Australia, Lord Gowrie, persuaded Bradman to transfer to the army, a move that was criticised as a safer option for him. Given the rank of lieutenant, he was posted to the Army School of Physical Training at Frankston, Victoria, to act as a divisional supervisor of physical training. The exertion of the job aggravated his chronic muscular problems, diagnosed as fibrositis. Surprisingly, a routine army test revealed that Bradman had poor eyesight.

Invalided out of service in June 1941, Bradman spent months recuperating, unable to shave himself or comb his hair due to muscular pain. He resumed stockbroking during 1942. In his biography of Bradman, Charles Williams expounded the theory that the physical problems were psychosomatic, induced by stress and possibly clinical depression. Bradman read the book's manuscript and did not disagree. Had any cricket been played at this time, he would not have been available. Although he found some relief in 1945 when referred to the Melbourne masseur Ern Saunders, Bradman permanently lost the feeling in the thumb and index finger of his right hand.

In June 1945, D. Bradman faced a financial crisis when the firm of Harry Hodgetts collapsed due to fraud and embezzlement. Many assumed that Bradman was complicit in the collapse; he was sometimes (erroneously) referred to as a partner of Hodgetts. Bradman moved quickly to set up his own business utilizing Hodgetts’ client list and his old office in Grenfell Street, Adelaide. The fallout led to a prison term for Hodgetts, and left a stigma attached to Bradman’s name in the city’s business community for many years.

However, the SA Cricket Association had no hesitation in appointing Bradman as their delegate to the Board of Control in place of Hodgetts. Now working alongside some of the men he had battled in the 1930s, Bradman quickly became a leading light in the administration of the game. He resumed his position as a Test selector, and played a major role in planning for post-war cricket.

"The ghost of a once great cricketer":

Bradman suffered regular bouts of fibrositis while coming to terms with increased administrative duties and the establishment of his business. He played for SA in two matches to help with the re-establishment of first-class cricket and later described his batting as “painstaking.” Batting against the Australian Services team, Bradman scored 112 in less than two hours, yet Dick Whitington (playing for the Services) wrote that, “I have seen today the ghost of a once great cricketer.” Bradman declined a tour of New Zealand and spent the winter of 1946 unsure if he had played his last match.

With the English team due to arrive for the Ashes series, the media and the public were anxious to know if Bradman would lead Australia. His doctor recommended against a return to the game. Encouraged by his wife, Bradman agreed to play in lead-up fixtures to the Test series. After hitting two centuries, Bradman made himself available for the first Test at The Gabba.

The pivotal moment of the Ashes contest came as early as the first day of the series. After compiling an unconfident 28 runs, Bradman hit a ball to the gully fieldsman, Jack Ikin. An appeal for a catch was contentiously denied, the umpire ruling it a bump ball. At the end of the over, England captain Wally Hammond had a verbal dig at Bradman, and “from then on the series was a cricketing war just when most people desired peace.” Bradman regained his finest pre-war form in making 187, following that with 234 during the second Test at Sydney. Australia won both matches by an innings. Jack Fingleton speculated that had the decision at Brisbane had gone against him, Bradman would have retired, such were his fitness problems.

In the remainder of the series, Bradman made three half-centuries in six innings, but was unable to make another century. Nevertheless, his team won handsomely by 3-0. He was the leading batsman on either side, with an average of 97.14. Nearly 850,000 spectators watched the Tests, which helped lift public spirits after the war.

Century of centuries and "The Invincibles":

India made its first tour of Australia in the 1947–48 season. On 15 November Bradman made 172 against them for an Australian XI at Sydney, his one hundredth first-class century. The first non-Englishman to achieve the milestone, Bradman remains the only Australian to do so. In five Tests, he scored 715 runs (at 178.75 average). His last double century (201) came at Adelaide, and he scored a century in each innings of the Melbourne Test. On the eve of the fifth Test, he announced that the match would be his last in Australia, although he would tour England as a farewell.

Australia had assembled one of the great teams of cricket history. Bradman made it known that he wanted to go through the tour unbeaten, a feat never before accomplished. English spectators were drawn to the matches knowing that it would be their last opportunity to see Bradman in action. RC Robertson-Glasgow observed of Bradman that:

"Next to Mr. Winston Churchill, he was the most celebrated man in England during the summer of 1948. His appearances throughout the country were like one continuous farewell matinée. At last his batting showed human fallibility. Often, especially at the start of the innings, he played where the ball wasn't, and spectators rubbed their eyes."

Despite his waning powers, Bradman compiled eleven centuries in his 2,428 runs (average 89.92). His highest score of the tour (187) came against Essex, when the team compiled a world record of 721 runs in a day. In the Tests, he scored a century at Nottingham, but his only truly vintage performance was in the fourth Test at Leeds. England declared on the last morning of the game, setting Australia a world record 404 runs to win in only 345 minutes on a heavily-worn wicket. In partnership with Arthur Morris (182), Bradman reeled off 173 not out and the match was won with fifteen minutes to spare. The journalist Ray Robinson called the victory “the 'finest ever' in its conquest of seemingly insuperable odds.”

In the final Test at The Oval, Bradman walked out to bat in Australia’s first innings, and received a standing ovation from the crowd and three cheers from the opposition. His Test batting average stood at 101.39. Facing the wrist-spin of Eric Hollies, Bradman pushed forward to the second ball that he faced, was deceived by a wrong 'un, and bowled between bat and pad for no score. An England batting collapse resulted in an innings defeat, denying Bradman the opportunity to bat again and so his average finished at 99.94 – just four runs short of an even hundred. The story perpetuated over many years that Bradman missed the ball because of tears in his eyes was a claim he denied for the rest of his life.

The Australian team won the Ashes 4–0, completed the tour unbeaten, and have entered history as “The Invincibles.” Just as Bradman’s legend grew, rather than diminished, over the years, so too has the reputation of the 1948 team. For Bradman, it was the most personally fulfilling period of his playing days, as the divisiveness of the 1930s had passed. He wrote:

"Knowing the personnel, I was confident that here at last was the great opportunity which I had longed for. A team of cricketers whose respect and loyalty were unquestioned, who would regard me in a fatherly sense and listen to my advice, follow my guidance and not question my handling of affairs ... there are no longer any fears that they will query the wisdom of what you do. The result is a sense of freedom to give full reign to your own creative ability and personal judgment."

After his return to Australia, Bradman played in his own Testimonial match at Melbourne, scoring his 117th and last century, and receiving ₤9,342 in proceeds. In the 1949 New Year’s Honours List, Bradman was made a Knight Bachelor for his services to the game, and the following year he published a memoir, Farewell to Cricket. Bradman accepted offers from the Daily Mail to travel with, and write about, the 1953 and 1956 Australian teams in England, but never succumbed to the lure of regular journalism. The Art of Cricket, his final book published in 1958, is an instructional manual that retains its relevance today.

In June 1954, Bradman retired from his stockbroking business and then earned a “comfortable” income as a board member of sixteen publicly-listed companies. His highest profile affiliation was with Argo Investments Limited, where he was Chairman for a number of years. Charles Williams commented that, "[b]usiness was excluded on medical grounds, [so] the only sensible alternative was a career in the administration of the game which he loved and to which he had given most of his active life".

The MCC awarded Bradman life membership in 1958 and his portrait hung in the Long Room at Lord's. He opened the “Bradman Stand” at the SCG in January 1974. Later that year, he attended a Lord's Taverners function in London where he experienced heart problems, which forced him to limit his appearances to select occasions only. With his wife, Bradman returned to Bowral in 1976, where the new cricket ground was named in his honour. He gave the keynote speech at the historic Centenary Test at Melbourne in 1977 and the following year he attended a reunion of his 1948 team, organised by the Primary Club charity. On 16 June 1979, the Australian government awarded Bradman the nation’s highest civilian honour, Companion of the Order of Australia (AC). In 1980, he resigned from the ACB and led a more secluded life.

Administrative career:

"Bradman was more than a cricket player nonpareil. He was [...] an astute and progressive administrator; an expansive thinker, philosopher and writer on the game. Indeed, in some respects, he was as powerful, persuasive and influential a figure off the ground as he was on it."

—Mike Coward

In addition to acting as South Australia's delegate to the Board of Control from 1945 to 1980, Bradman was a committeeman of the SACA between 1935 and 1986. It is estimated that he attended 1,713 SACA meetings during this half century of service. Aside from two years in the early 1950s, he filled a selector's berth for the Test team between 1936 and 1971.

Cricket suffered an increase in defensive play during the 1950s. As a selector, Bradman favoured attacking, positive cricketers who entertained the paying public. He formed an alliance with Australian captain Richie Benaud, seeking more attractive play. The duo was given much of the credit for the exciting 1960–61 tour by the West Indies, which included the first-ever tied Test, played at Brisbane.

He served two high-profile periods as Chairman of the Board of Control, in 1960–63 and 1969–72. During the first, he dealt with the growing prevalence of illegal bowling actions in the game, a problem that he adjudged "the most complex I have known in cricket, because it is not a matter of fact but of opinion". The major controversy of his second stint was a proposed tour of Australia by South Africa in 1971–72. On Bradman's recommendation, the series was cancelled.

In the late 1970s, Bradman played an important role during the World Series Cricket schism as a member of a special Australian Cricket Board committee formed to handle the crisis. He was criticised for not airing an opinion, but he dealt with World Series Cricket far more pragmatically than other administrators. Richie Benaud, in his capacity as a consultant to WSC, prepared a document on the inner workings of official cricket. In it, he described Bradman as "a brilliant administrator and businessman", warning that he was not to be underestimated.

As Australian captain, Ian Chappell fought with Bradman over the issue of player remuneration in the early 1970s. Chappell has recently commented that Bradman should have been more empathetic toward the players, considering his own clashes with administrators during the 1930s. While Chappell has suggested that Bradman was responsible for the split, and that he was parsimonious and treated the ACB's money as his own, Gideon Haigh considers that Bradman was merely applying the standards of his own generation without taking into account that society (and sport) had changed:

Bradman's playing philosophy—that cricket should not be a career, and that those good enough could profit from other avenues—also seems to have borne on his approach to administration. Biographers have disserved Bradman in glossing over his years in officialdom. His strength and scruples over more than three decades were exemplary; the foremost master of the game became its staunchest servant. But he largely missed the secular shift toward the professionalisation of sport in the late '60s and early '70s, which finally found expression in Kerry Packer's World Series Cricket [....] Discussing Packer, Bradman told biographer Charles Williams in January 1995 he "accepted that cricket had to become professional".

Later years and legacy:

Cricket writer David Frith summed up the paradox of the continuing fascination with Bradman:

"As the years passed, with no lessening of his reclusiveness, so his public stature continued to grow, until the sense of reverence and unquestioning worship left many of his contemporaries scratching their heads in wondering admiration."

Although he was modest about his own abilities and generous in his praise of other cricketers, “Bradman knew perfectly well how great a player he had been”. In his latter years, Bradman carefully selected the people to whom he gave interviews, in an attempt to influence his legacy. He assisted Michael Page, Roland Perry and Charles Williams, who all produced biographical works about Bradman during the 1980s and 1990s. Bradman agreed to an extensive interview for ABC radio, broadcast as Bradman: The Don Declares in eight 55-minute episodes during 1988.

After his wife's death in 1997, Bradman suffered “a discernable and not unexpected wilting of spirit”. On his ninetieth birthday, he hosted a meeting with his two favourite modern players, Shane Warne and Sachin Tendulkar, but he was not seen in his familiar place at the Adelaide Oval again. Hospitalised with pneumonia in December 2000, he returned home in the New Year and died there on 25 February 2001.

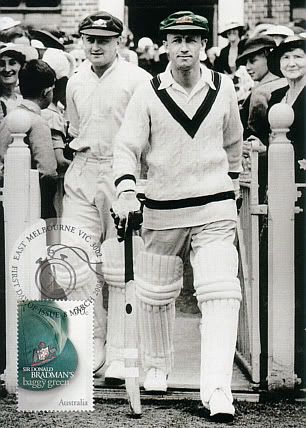

Bradman was the first living Australian featured on an Australian postage stamp, issued in 1997. In 2001, a major arterial road in Adelaide was re-named Sir Donald Bradman Drive. After his death, the Australian Government produced a 20 cent coin to commemorate his life.

Family life:

This collection of Bradman's private letters published in 2004 has given researchers new insights into Bradman's personal life.The Bradmans lived in the same modest, suburban house in Holden Street, Kensington Park in Adelaide for all but the first three years of their married life. They experienced much personal tragedy in raising their children. Their first-born son died less than 48 hours after he was born and their second son, John (born in 1939) contracted polio during an epidemic of the disease that swept Adelaide in the summer of 1951–52. Their daughter Shirley was born in 1941 with cerebral palsy. Bradman attempted to keep his children away from the limelight as much as possible.

However, the burden of his family name proved too great for John Bradman to handle. After studying law and qualifying as a barrister, he changed his last name to Bradsen by deed poll in 1972. He went on to a distinguished career as a lecturer in law at Adelaide University. Although claims were made that he became estranged from his father, it was more a matter of “the pair inhabit[ing] different worlds”.After his death, a collection of personal letters written by Bradman to his close friend Rohan Rivett between 1953 and 1977 was released and gave researchers new insights into Bradman’s family life. The letters detail the strain between father and son.

Bradman’s reclusiveness in later life is partly attributable to the on-going health problems of his wife. Jessie had open-heart surgery in her sixties and later needed a hip replacement. She died in 1997 from leukaemia. This had a dispiriting effect on Bradman, but the upside was a strengthening of his relationship with his son. The pair became much closer in Bradman’s last years and John resolved to change his name back to Bradman. Since his father’s death, John Bradman has become the spokesperson for the family and has been involved in defending Bradman in a number of disputes about the Bradman legacy.

The relationship between Bradman and his parents and siblings is less clear. Little biographical information on them is available from the period after Bradman moved to Adelaide. Nine months after Bradman’s death, his nephew Paul Bradman criticised him as a “snob” and a “loner” who forgot his connections in Bowral, and who failed to attend the funerals of his mother and father.

*Acknowledgements to Wikipedia.org, Cricinfo.com and owners of pictures and videos used.

Wednesday, April 16, 2008

Player Profile(#18)...Don Bradman(Australia)

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

No comments:

Post a Comment